Int J Aging. 2023;1:e4.

doi: 10.34172/ija.2023.e4

Original Article

The Burden of Low Back Pain Among Adults Aged 70 and Older in Iran, 1990-2019

Reza Aletaha 1  , Seyed Ehsan Mousavi 2, Ali Shamekh 2, Seyed Aria Nejadghaderi 3, 4

, Seyed Ehsan Mousavi 2, Ali Shamekh 2, Seyed Aria Nejadghaderi 3, 4  , Mark J. M. Sullman 5, 6, Ali-Asghar Kolahi 7, *

, Mark J. M. Sullman 5, 6, Ali-Asghar Kolahi 7, *

Author information:

1Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Research Center for Integrative Medicine in Aging, Aging Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Expert Group (SRMEG), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Tehran, Iran

5Department of Life and Health Sciences, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

6Department of Social Sciences, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

7Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Objectives:

To report the burden of low back pain (LBP) among those aged 70 and above in Iran by age, sex, and province from 1990 to 2019.

Design:

Systematic analysis.

Outcome measures:

Data were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019. All estimates were reported as counts and age-standardized rates per 100000 individuals, with their corresponding 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs).

Results:

In 2019, LBP had a point prevalence of 21714.8 and an incidence rate of 8097.7 per 100000 population among adults aged 70 and older above in Iran. In 2019, the number of years lived with disability (YLDs) and the YLD rate due to LBP were 78.2 thousand and 2252.3, respectively. From 1990 to 2019, the prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates did not change substantially over the measurement period. Mazandaran and East Azarbayejan had the highest and lowest YLD rates per 100000 with rates of 3229.8 and 1912.7, respectively, in adults aged 70 and older. In 2019, the prevalent cases, incident cases, and YLDs along with their corresponding rates due to LBP did not differ significantly among males and females in the geriatric population of Iran. Furthermore, in 2019, the 70–74-year-old group had the highest number of prevalent cases, incident cases, and YLDs for both sexes, and all decreased with increasing age.

Conclusions:

Although the rates of LBP have not changed substantially over the last three decades, the burden among the geriatric population of Iran remains high. Therefore, preventive and therapeutic measures are needed to help reduce the burden among the geriatric population in Iran.

Keywords: Low back pain, Global burden of disease, Geriatrics, Iran, Epidemiology

Introduction

In recent years, the increasing life expectancy in Iran has accelerated the shift from communicable to non-communicable diseases such as musculoskeletal disorders.1,2 In accordance with the global burden of musculoskeletal disorders, the prevalence of these disorders is relatively high in Iran, especially among the elderly.3 Previous research in Iran has reported that musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most common causes of disability among both sexes.3

Using Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017 data, previous research showed that low back pain (LBP) was the most common musculoskeletal cause of disability,4 the third leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) among Iranians aged 15 to 69.5 LBP imposes a substantial financial burden, which includes the cost of medical care, productivity loss, indemnity payments, administrative expenses, and employee retraining.6-8 Although LBP is considered to be almost inevitable among the elderly, this condition can be ameliorated or avoided by making appropriate lifestyle adjustments. Poor nutrition, excess body weight, and smoking are among the most important modifiable risk factors for LBP.9 In the past twenty years, the LBP-related YLDs for all ages have increased by 83% in Iran, which is almost twice the global average increase.3 This fact demonstrates that there is an urgent need for effective healthcare interventions. This is especially the case in the less developed areas of Iran, particularly taking into consideration the large physical and financial burden attributed to LBP, which will greatly increase in the coming years due to the rapidly increasing life expectancy and population aging.9 In order to design appropriate strategies to improve the health of the elderly, efficiently allocate resources, and prioritize interventions, it is vital to understand the trends of the disease burden among the elderly.10

A small number of studies have estimated the LBP-attributable burden in low- and middle-income countries.11,12 A recent cohort study reported the prevalence and risk factors associated with LBP among those aged 35 to 70 years old from 16 different provinces of Iran using information from the Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (PERSIAN).13 However, no previous research has reported the burden of LBP in the Iranian geriatric age population using modeling strategies. Therefore, the present study aimed to report the burden of LBP among adults aged 70 and older in Iran according to age, sex, and location over the past three decades.

Methods

Overview

The GBD is a comprehensive global and regional research program that collects information on the burden of diseases and injuries in 204 countries.14,15 The current study provided data on the prevalence, incidence, and YLDs attributable to LBP in Iran as well as its 31 provinces from 1990 to 2019. Further details about the figures used in the present study are available online at the following website http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Case Definition and Data Sources

LBP was defined in the present study as LBP (with or without pain transferred into one or both lower limbs) that lasts for one or more days. The “low back” is the region on the posterior portion of the body from the lower margin of the twelfth ribs to the lower gluteal folds.14 The International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes for LBP were used, including both versions 9 (724) and 10 (M54.3, M54.4, and M54.5).14 An update to the LBP’s previous systematic review was carried out by Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) from October 2016 to October 2017, which involved searching the databases such as Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Ovid Medline, PubMed, and Ovid Medline. Identified studies would be excluded if they had small sample sizes ( < 150), did not use samples that were representative of the general population, or did not publish original data. In addition, several studies were identified and evaluated during the data review process, and the GBD database of surveys (Global Health Data Exchange), which includes World Health surveys and national health surveys, was also searched.

Data Processing and Disease Model

Where practical, the prevalence estimates were separated by sex and age. If prevalence is reported for broad age groups by sex or by age groups with males and females combined, then age-specific estimates will be separated into sex-specific estimates using their reported sex ratios and bounds of uncertainty. In studies that did not provide a within-study sex ratio, cases were separated using a sex ratio produced by a meta-analysis of LBP studies using MR-BRT (a meta-regression tool). Finally, in studies that reported estimates using age groups of 25 years or above, the descriptive epidemiological meta-regression tool (DisMod-MR) 2.1 used the prevalence age pattern found in GDB 2017 to divide the estimates into five-year age groups. DisMod-MR 2.1 was also used to estimate the prevalence and incidence of LBP with excess mortality set to 0. The same country-level covariates and modeling approaches were used in GBD 2019 in the same way used in GBD 2017.14

Years Lived with Disability

The most substantial functional effects and symptoms of LBP were identified using the GBD Disability Weight Survey, which provides lay descriptions of the different sequelae.14 The DALYs attributable to LBP were estimated by combining the years of life lost (YLLs) and the YLDs.14 The YLD and DALY estimates were the same since there was no evidence that LBP was responsible for any fatalities.14 The LBP-related YLDs were estimated by multiplying the severity-specific prevalence estimates by their corresponding disability weights.

Compilation of Results

Ninety-five percent uncertainty intervals (UIs) were calculated for all estimations by running 1000 draws at each computing step and combining uncertainty from several sources (e.g., input data, measurement error, and estimated residual non-sampling error). The UIs consisted of the 25th and 975th values of the ordered draws. Moreover, age was divided into six categories: 70-74, 75-79, 80-84, 85-89, 90-94, and 95 plus. Then, the statistical program R was used for all statistical analyses (Version 3.6.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

National Level

In 2019, there were 753.9 thousand (95% UI: 613.5 to 924.6 thousand) prevalent cases of LBP among adults aged 70 and older in Iran, and a point prevalence of 21714.8 per 100 000 (95% UI: 17671 to 26630.4). There were also 281.1 thousand (95% UI: 220.4 to 351.8 thousand) incident cases and an incidence rate of 8097.7 per 100 000 (95% UI: 6348.1 to 10131.5). Furthermore, the YLDs and the YLD rates were 78.2 thousand (95% UI: 55 to 106 thousand) and 2252.3 per 100 000 (95% UI: 1583.8 to 3054.3), respectively. Further, the prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates did not change substantially over the period from 1990 to 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence, Incident Cases, and YLDs due to LBP for Adults Aged 70 and Above in 1990 and 2019 for Both Sexes and Percentage Change in Rates per 100 000 in Iran

|

|

Prevalence (95% UI)

|

Incidence (95% UI)

|

YLDs (95% UI)

|

Counts

(2019)

|

Rate

(2019)

|

Pcs in rate

1990-2019

|

Counts

(2019)

|

Rate

(2019)

|

Pcs in rate

1990-2019

|

Counts

(2019)

|

Rate

(2019)

|

Pcs in rate

1990-2019

|

| Iran |

753922 (613525, 924587) |

21714.8 (17671, 26630.4) |

-4.9 (-11.7, 3.7) |

281145 (220402, 351757) |

8097.7 (6348.1, 10131.5) |

-4.1 (-11.2, 5.6) |

78198 (54988, 106042) |

2252.3 (1583.8, 3054.3) |

-5.9 (-13.3, 3.2) |

| Alborz |

22299 (17763, 27856) |

20597.1 (16407.5, 25730.7) |

-6.3 (-14, 2.1) |

8606 (6610, 10869) |

7949.7 (6105.6, 10040) |

-4.1 (-11.3, 4.2) |

2330 (1597, 3225) |

2152 (1475.5, 2979.1) |

-7.1 (-15.4, 1.9) |

| Ardebil |

11939 (9687, 14719) |

21193.4 (17195.9, 26127.5) |

-6 (-14.8, 4.3) |

4541 (3555, 5663) |

8061.5 (6310.2, 10053.3) |

-4.2 (-11.9, 5) |

1241 (862, 1691) |

2203.1 (1529.3, 3001.3) |

-6.4 (-15.9, 4.4) |

| Bushehr |

7580 (6047, 9563) |

20535.6 (16381, 25905.4) |

-5.7 (-14, 3.3) |

2934 (2263, 3722) |

7948.6 (6130.3, 10083.8) |

-4 (-11.9, 4.7) |

793 (545, 1094) |

2147.2 (1475.5, 2964.2) |

-6.3 (-15.1, 2.9) |

| Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari |

7849 (6399, 9732) |

20837.5 (16989.7, 25836.9) |

-6 (-15.4, 5.9) |

3001 (2321, 3745) |

7968 (6162.9, 9943.8) |

-4.9 (-14.1, 7.1) |

818 (568, 1118) |

2172.5 (1506.7, 2969.2) |

-6.8 (-17.4, 6.4) |

| East Azarbayejan |

33972 (25890, 43522) |

18376.5 (14004.6, 23542) |

-8.3 (-19.4, 6.4) |

13678 (10289, 17501) |

7398.8 (5565.3, 9466.8) |

-5.6 (-15.7, 7.4) |

3536 (2391, 4886) |

1912.7 (1293.4, 2642.9) |

-9.7 (-21, 5.8) |

| Fars |

41284 (33185, 50902) |

20669.1 (16614.4, 25484.2) |

-6.4 (-14.6, 4.3) |

15825 (12404, 19704) |

7922.7 (6210, 9864.8) |

-5.1 (-13.3, 4.2) |

4300 (3005, 5885) |

2152.9 (1504.7, 2946.4) |

-6.8 (-15.4, 4.4) |

| Gilan |

32631 (26037, 40690) |

20922.2 (16694.6, 26089.8) |

-6.3 (-15.5, 5.6) |

12475 (9783, 15601) |

7998.8 (6272.4, 10003.1) |

-5.2 (-14.6, 7.4) |

3388 (2323, 4632) |

2172.2 (1489.4, 2970.1) |

-7.5 (-17.6, 5.6) |

| Golestan |

12896 (10352, 15989) |

21001.9 (16858.2, 26039.1) |

-6.5 (-15, 3.6) |

4920 (3844, 6170) |

8012.6 (6259.6, 10048.7) |

-4.9 (-12.9, 5.2) |

1342 (936, 1821) |

2185.1 (1523.8, 2965.7) |

-7.7 (-16.9, 3.3) |

| Hamadan |

19752 (16033, 24695) |

20914.3 (16977.2, 26148.5) |

-6.4 (-16.4, 6.4) |

7544 (5852, 9404) |

7987.7 (6196.8, 9957.4) |

-5.1 (-15.4, 7.4) |

2058 (1437, 2829) |

2179.5 (1521.6, 2995.1) |

-7.3 (-17.6, 5.9) |

| Hormozgan |

10394 (8349, 12817) |

20676.6 (16608, 25495.3) |

-7.1 (-15.8, 2.4) |

3979 (3117, 4936) |

7915.3 (6199.6, 9818.6) |

-5.6 (-14.2, 3.8) |

1084 (755, 1473) |

2156.8 (1501.6, 2930) |

-8 (-16.9, 2.2) |

| Ilam |

3900 (3124, 4810) |

20902.2 (16745.1, 25783.5) |

-6.2 (-13.6, 3.1) |

1493 (1162, 1871) |

8002.5 (6227, 10029) |

-4.2 (-11.6, 4.3) |

408 (282, 555) |

2186 (1511.1, 2975.6) |

-6.6 (-14.2, 2.2) |

| Isfahan |

51960 (41722, 64361) |

20585.4 (16529.2, 25498.5) |

-5.9 (-14.7, 5) |

19970 (15469, 24924) |

7911.7 (6128.6, 9874.5) |

-4.9 (-14.6, 5.5) |

5405 (3729, 7441) |

2141.5 (1477.1, 2947.9) |

-7.4 (-16.7, 3.6) |

| Kerman |

23266 (18740, 28807) |

21009.5 (16922.4, 26012.8) |

-5.9 (-16, 7.5) |

8877 (6959, 11180) |

8015.6 (6283.8, 10096) |

-4.9 (-14.6, 7.4) |

2399 (1662, 3276) |

2166.3 (1500.9, 2957.9) |

-7.2 (-18, 6.9) |

| Kermanshah |

17863 (14500, 21994) |

20800.3 (16884.4, 25610.4) |

-6.7 (-15.3, 3) |

6797 (5302, 8510) |

7914.2 (6173.9, 9909) |

-5.7 (-14.2, 4.6) |

1856 (1282, 2514) |

2160.9 (1492.9, 2927) |

-8.1 (-17.1, 2.8) |

| Khorasan-e-Razavi |

55051 (43970, 68161) |

20828.5 (16636, 25788.9) |

-6.5 (-16.5, 5.2) |

21147 (16306, 26474) |

8000.9 (6169.2, 10016.3) |

-5 (-14.4, 6.7) |

5632 (3922, 7693) |

2130.7 (1483.8, 2910.8) |

-8.6 (-19.2, 3.9) |

| Khuzestan |

33276 (26709, 41744) |

20667.6 (16588.8, 25927.4) |

-6.8 (-14.2, 1.1) |

12783 (9968, 15970) |

7939.7 (6191.1, 9919) |

-5.1 (-12, 3.4) |

3448 (2394, 4709) |

2141.5 (1486.8, 2924.7) |

-6.9 (-14.7, 1.4) |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad |

4388 (3518, 5408) |

20613.7 (16527.2, 25405.9) |

-7.2 (-16.3, 3.3) |

1672 (1311, 2092) |

7855.9 (6160.1, 9827.7) |

-6 (-14.3, 4.8) |

457 (315, 621) |

2148.3 (1479.4, 2918) |

-7.1 (-16.6, 4) |

| Kurdistan |

14197 (11513, 17570) |

20899 (16947.5, 25863.6) |

-6.9 (-14.7, 1.5) |

5409 (4244, 6701) |

7962.1 (6247.6, 9863.7) |

-5.2 (-12.7, 3.9) |

1483 (1033, 2023) |

2183.6 (1520.3, 2978) |

-7.6 (-15.8, 1.6) |

| Lorestan |

15302 (12387, 19089) |

20971.1 (16977.1, 26161.2) |

-6.4 (-16.2, 3.9) |

5846 (4582, 7311) |

8011.8 (6279.3, 10019.6) |

-4.7 (-13.4, 4.1) |

1599 (1115, 2175) |

2191.1 (1528.1, 2981.1) |

-6.4 (-16.1, 4.6) |

| Markazi |

17415 (14208, 21486) |

20774.7 (16949.1, 25631.9) |

-6.1 (-16, 6.3) |

6640 (5229, 8236) |

7920.9 (6237.9, 9824.9) |

-5.1 (-15.9, 7.9) |

1802 (1251, 2441) |

2149.4 (1492.7, 2912.3) |

-6.9 (-17.6, 6.7) |

| Mazandaran |

55225 (45957, 65886) |

31403.9 (26133.6, 37466.3) |

-4.1 (-12, 5.3) |

15997 (12492, 20169) |

9096.5 (7103.4, 11469.2) |

-4.2 (-13.3, 7.5) |

5680 (4015, 7560) |

3229.8 (2282.9, 4299.3) |

-4.9 (-13.1, 5.4) |

| North Khorasan |

7397 (5979, 9165) |

20945.7 (16930.1, 25951) |

-6.8 (-16.5, 5.2) |

2818 (2192, 3522) |

7980.1 (6206.2, 9972.4) |

-6 (-15.3, 6.3) |

765 (535, 1039) |

2166.3 (1515.8, 2941.9) |

-8.3 (-17.8, 4.5) |

| Qazvin |

11327 (9145, 13999) |

20836.1 (16821.7, 25750.6) |

-6.5 (-14.7, 5.2) |

4336 (3361, 5428) |

7975.5 (6182.8, 9984.6) |

-5.3 (-15.2, 7.2) |

1181 (822, 1620) |

2171.7 (1511.5, 2980.1) |

-7.4 (-16.2, 5) |

| Qom |

9694 (7752, 12028) |

20310.2 (16241.1, 25198.9) |

-6 (-14.8, 3.6) |

3755 (2939, 4701) |

7866.7 (6157.5, 9848.3) |

-4.2 (-13.3, 5.6) |

1008 (699, 1386) |

2112.2 (1464.8, 2902.8) |

-5.7 (-14.4, 5.1) |

| Semnan |

6996 (5655, 8737) |

20696.6 (16728.5, 25845.4) |

-6.2 (-14.9, 5.7) |

2698 (2109, 3390) |

7981.1 (6239.3, 10027.4) |

-4.6 (-13.9, 6.5) |

728 (500, 983) |

2153.5 (1480.5, 2908.7) |

-6.4 (-16.4, 6.1) |

| Sistan and Baluchistan |

11694 (9490, 14415) |

20568.8 (16691.7, 25355) |

-6.7 (-16.1, 3.5) |

4482 (3532, 5571) |

7883.6 (6212.8, 9798.1) |

-5.8 (-15.4, 6.4) |

1215 (860, 1670) |

2137.2 (1513.3, 2937.1) |

-8.1 (-18, 3.6) |

| South Khorasan |

8463 (6752, 10416) |

21074.7 (16813.3, 25938.2) |

-5.8 (-15.9, 6.2) |

3220 (2518, 4036) |

8019.4 (6271, 10049.4) |

-4.7 (-14.3, 7.3) |

871 (592, 1185) |

2168.8 (1475.1, 2951.7) |

-7.5 (-17.9, 5.1) |

| Tehran |

159950 (131198, 194849) |

23363.1 (19163.4, 28460.6) |

-2.1 (-11.1, 8.1) |

58148 (45930, 72786) |

8493.4 (6708.7, 10631.4) |

-1.8 (-9.8, 8.1) |

16597 (11789, 22402) |

2424.2 (1721.9, 3272.2) |

-3.1 (-12.2, 7.6) |

| West Azarbayejan |

25155 (20217, 31194) |

21153.4 (17001.2, 26232.1) |

-5.8 (-14.1, 4.7) |

9604 (7434, 12047) |

8075.9 (6251.4, 10130.9) |

-4.3 (-13.2, 6.4) |

2619 (1822, 3592) |

2202 (1532.6, 3020.6) |

-6.7 (-15.6, 4.2) |

| Yazd |

9709 (7796, 11971) |

20716.9 (16633.9, 25541.8) |

-5.9 (-15.4, 5.6) |

3722 (2944, 4630) |

7942.3 (6281, 9877.8) |

-4.9 (-14.3, 6.7) |

1004 (698, 1372) |

2142.2 (1490.3, 2927.8) |

-6.7 (-17.2, 5.9) |

| Zanjan |

11096 (8926, 13678) |

21109.2 (16981.7, 26021.8) |

-6.1 (-15.5, 5.5) |

4228 (3279, 5286) |

8043.4 (6238, 10056.3) |

-4.7 (-14.2, 7.6) |

1152 (800, 1572) |

2192.4 (1522.6, 2991.5) |

-7 (-17.2, 6) |

Note. YLD: Years lived with disability; LBP: Low back pain; UI: Uncertainty intervals; Pcs: Percentage change.

Provincial Level

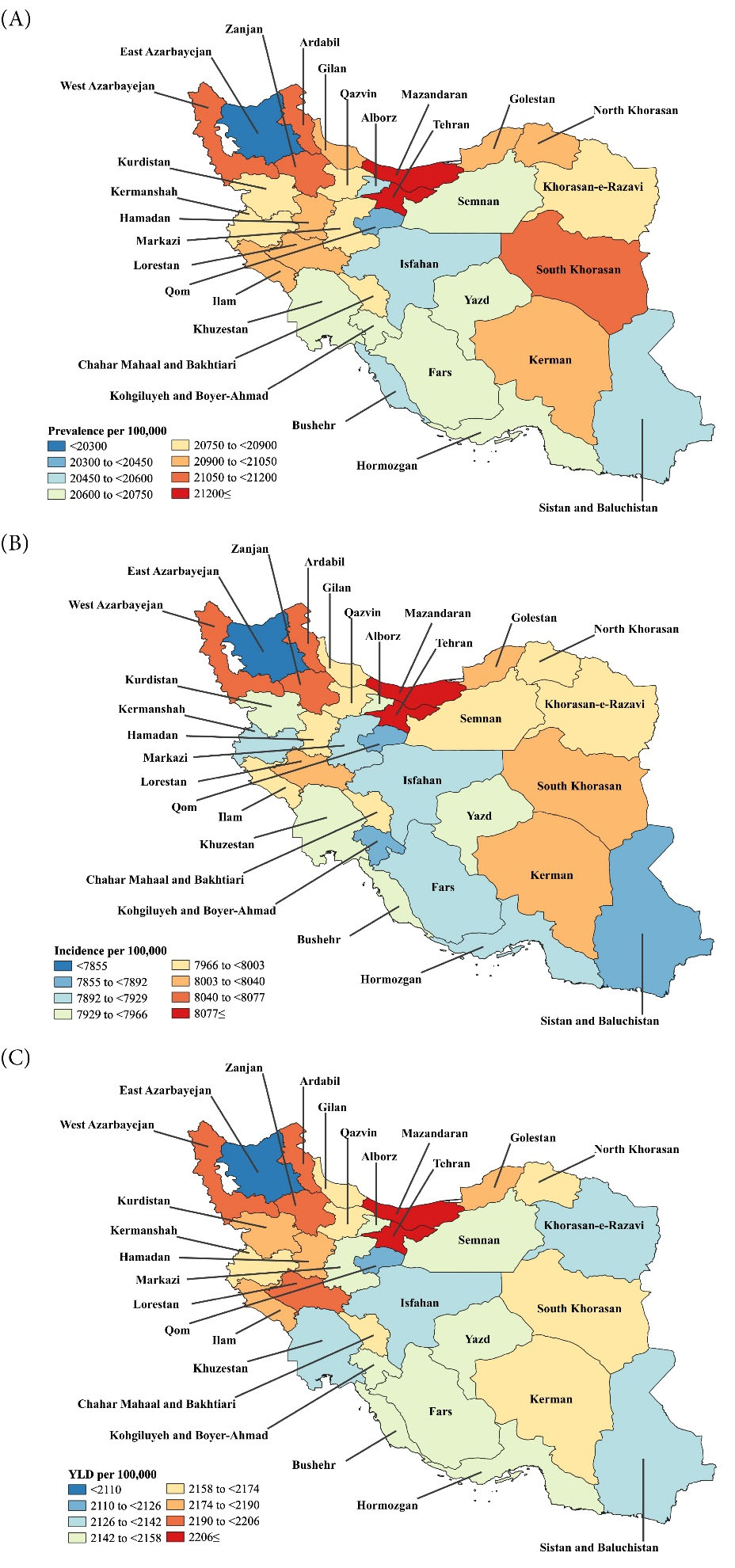

In 2019, Tehran (159 950; 95% UI: 131 198 to 194 849), Mazandaran (55 225; 95% UI: 45 957 to 65 886), and Khorasan-e-Razavi (55 051; 95% UI: 43 970 to 68 161) had the highest prevalent cases of LBP. In contrast, the lowest number of prevalent cases were found in Ilam (3900; 95% UI: 3124 to 4810), Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad (4388; 95% UI: 3518 to 5408), and North Khorasan (7397; 95% UI: 5979 to 9165). In addition, in 2019, the highest point prevalence per 100 000 population was observed in Mazandaran (31 403.9; 95% UI: 26 133.6 to 37 466.3), Tehran (23 363.1; 95% UI: 19 163.4 to 28 460.6), and Ardebil (21 193.4; 95% UI: 17 195.9 to 26 127.5), while the lowest point prevalence was reported for East Azarbayejan (18376.5; 95% UI: 14 004.6 to 23 542), Qom (20310.2; 95% UI: 16 241.1 to 25 198.9), and Bushehr (20535.6; 95% UI: 16 381 to 25 905.4) (Figure 1A and Table S1).

Figure 1.

(A) Point Prevalence, (B) Incidence, and (C) YLD Rates for LBP (per 100 000 population) for Adults 70 Years and Older in Iran in 2019 by Province. Note. YLD = Years lived with disability; LBP: Low back pain. Generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

.

(A) Point Prevalence, (B) Incidence, and (C) YLD Rates for LBP (per 100 000 population) for Adults 70 Years and Older in Iran in 2019 by Province. Note. YLD = Years lived with disability; LBP: Low back pain. Generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

At the provincial level, the 2019 sex-specific estimates for the point prevalence of LBP (per 100 000) among elderly Iranians ( > 70 years old) are presented in Figure S1. The sex differences in the point prevalence were not significant, except for Mazandaran, where the rate was significantly higher among women than among men.

In 2019, Mazandaran (9096.5; 95% UI: 7103.4 to 11469.2), Tehran (8493.4; 95% UI: 6708.7 to 10631.4), and Ardebil (8061.5; 95% UI: 6310.2 to 10053.3) had the highest incidence rates of LBP per 100 000. In contrast, the lowest incidence rates were found in East Azarbayejan (7398.8; 95% UI: 5565.3 to 9466.8), Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad (7855.9; 95% UI: 6160.1 to 9827.7), and Qom (7866.7; 95% UI: 6157.5 to 9848.3) (Figure 1B and Table S2). At the provincial level, the 2019 sex-specific estimates for the incidence rate of LBP (per 100 000) are presented in Figure S2, indicating no significant differences between the male and female incidence rates between the provinces.

Moreover, Mazandaran (3229.8; 95% UI: 2882.9 to 4299.3), Tehran (2424.2; 95% UI: 1721.9 to 3272.2), and Ardebil (2203.1; 95% UI: 1529.3 to 3001.3) had the highest YLD rates of LBP per 100 000 in 2019. Furthermore, the lowest YLD rates were found in East Azarbayejan (1912.7; 95% UI: 1293.4 to 2642.9), Qom (2112.2; 95% UI: 1464.8 to 2902.9), and Khorasan-e-Razavi (2130.7; 95% UI: 1483.8 to 2910.8) (Figure 1C and Table S3). At the provincial level, the 2019 sex-specific estimates for the YLD rate of LBP (per 100 000) are presented in Figure S3. It was found that the YLD rates do not differ significantly by sex, except for Mazandaran, where women had a significantly higher rate compared to men.

Age and Sex Patterns

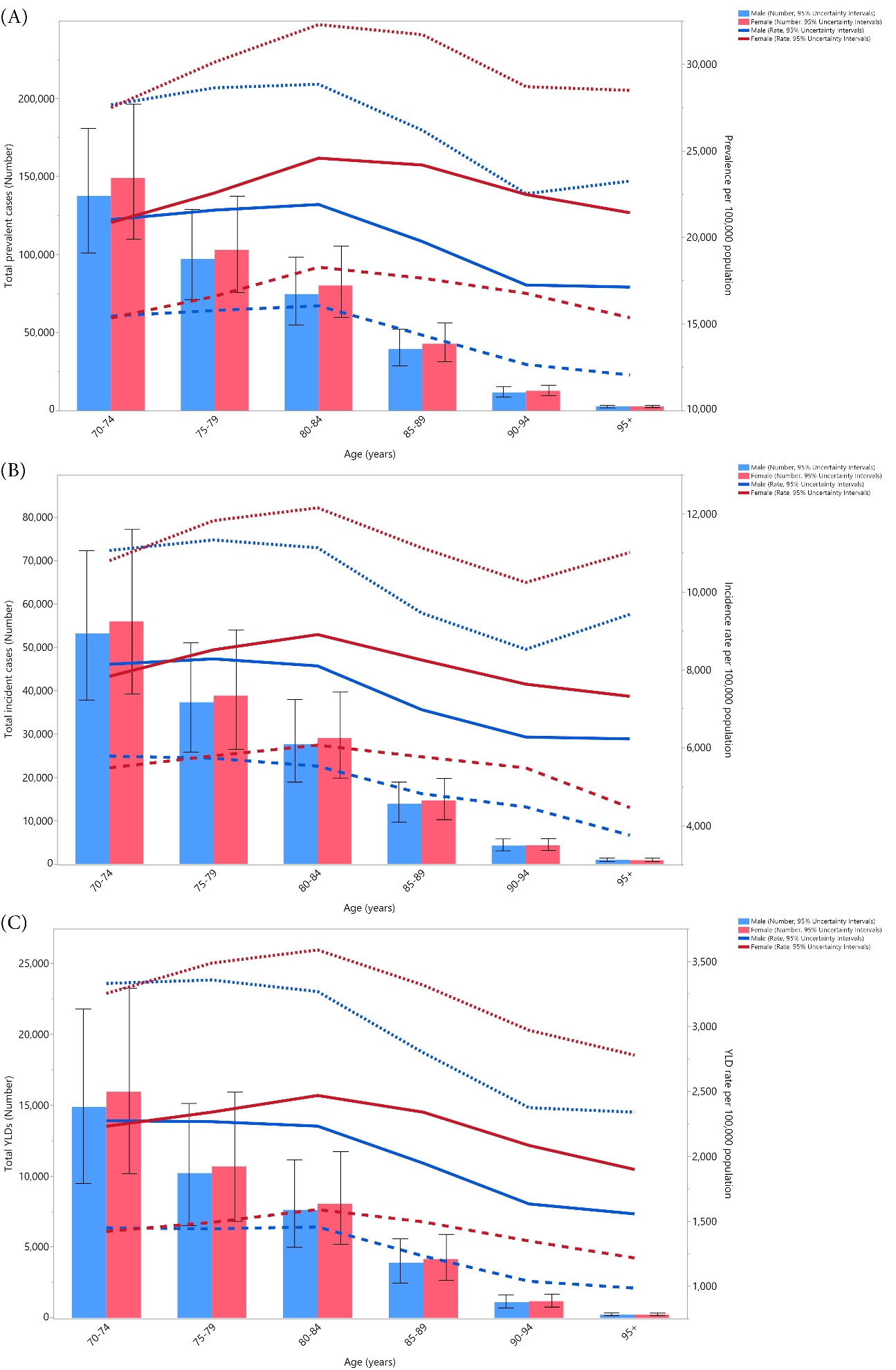

In 2019, the national prevalent cases, incident cases, YLDs, and their associated rates, did not differ significantly by sex. The total prevalent cases of LBP peaked in the 70-74 age group for both sexes and then decreased with increasing age. The point prevalence peaked for both sexes in the 80-84 age group and then decreased with advancing age (Figure 2A). Furthermore, there were no significant changes in the prevalence rates for both sexes between 1990 and 2019 in any of Iran’s provinces (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

(A) The Number of Prevalent Cases and Prevalence, (B) The Number of Incident Cases and Incidence Rate, and (C) the Number of YLDs and YLD rate for LBP (per 100 000 population) in Iran in 2019 by Age and Sex. Note. YLD = Years lived with disability; LBP: Low back pain. Dotted and dashed lines indicate 95% upper and lower UIs, respectively. Generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

.

(A) The Number of Prevalent Cases and Prevalence, (B) The Number of Incident Cases and Incidence Rate, and (C) the Number of YLDs and YLD rate for LBP (per 100 000 population) in Iran in 2019 by Age and Sex. Note. YLD = Years lived with disability; LBP: Low back pain. Dotted and dashed lines indicate 95% upper and lower UIs, respectively. Generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

The incidence rate of LBP in females peaked in the 80-84 age group and then decreased with advancing age. In contrast, males peaked in the 75-79 age group and then decreased with increasing age. In addition, the 70-74 age group had the highest number of incident cases for both sexes, which decreased with advancing age (Figure 2B), and there were no significant differences between the two sexes. Further, at the provincial level, there were no significant differences between the two sexes in terms of the changes in incidence from 1990 to 2019 (Figure S5).

In females, the YLD rate of LBP increased up to the 80-84 age group and then decreased with advancing age, while the YLD rate was highest in men in the 70-74 age group, and the rate decreased with advancing age. In addition, the 70-74 age group had the highest number of YLDs for both sexes and decreased with advancing age (Figure 2C). Moreover, there were no significant differences between the two sexes. Furthermore, at the provincial level, there were no significant changes in the male and female YLDs from 1990 to 2019 (Figure S6).

Discussion

The present study used GBD 2019 data to estimate the prevalence, incidence, and YLD counts as well as their corresponding rates for LBP in Iranian adults aged 70 by province from 1990 to 2019. In total, there were 753.9 thousand prevalent cases, 281.1 thousand incident cases, and 78.2 thousand YLDs among adults aged 70 and older in Iran. In addition, we found that the prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates did not change significantly over the study period or regarding sex.

The estimated prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates of LBP in the geriatric population of Iran were much higher than the global rates among the general population. Globally, the prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates per 100 000 were 6972.5, 2748.9, and 780.2, respectively, which were significantly lower than the estimates reported in the present study 16. Since aging is one of the most important risk factors of LBP,17-19 the rates in the current study are much higher than the global estimates among the general population. Several other reasons might explain these high rates, which include the increases in life expectancy, improvements in the healthcare system, the coverage at the population level, as well as improvements in the diagnosis of this condition over the measurement period. One of the main causes of LBP is intervertebral disc degeneration, and the degree of degeneration increases with advancing age, which might be an explanation for the observed age trend.20-22 In addition, aging is associated with more pain, which can affect many organs, limit physical and social function, speed up the degeneration of the musculoskeletal system, and in turn cause more pain.23 This loop can provide another explanation for the age trend. Nevertheless, Iran is a developing country, and according to previous research, the development level of countries and their socio-economic status are among the most important factors that contribute to the LBP burden.16

The previous three studies that were conducted in Iran in 2012,24 2017,17 and 202213 reported the prevalence of LBP to be 29.3%, 27%, and 25.2%, respectively. However, there are several differences between our study and the previous studies, including the larger sample size in the current study. In addition, several studies have evaluated LBP within a few months of the pain initiation,17,24 while the present study covers most of the related age groups over 30 years, accounting for LBP in its different phases. Moreover, it should also be noted that the results of this study were derived using advanced modeling techniques. Chen et al found that the global prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates due to LBP do not change greatly in the general population between 1990 and 2019.16 Similarly, the current research revealed that this trend is also evident among the elderly population of Iran.

The present study showed that the overall prevalence and incidence rates of LBP in the geriatric population of Iran were highest in Mazandaran, followed by Tehran and Ardebil provinces. The first two mentioned provinces also had the largest YLD rates. A cross-sectional study of 16 provinces in Iran (N = 163 770) indicated that the Mazani ethnicity has the strongest association with LBP.13 Perhaps the reason for this finding is due to their predominant general occupation as most of them work in rice cultivation fields. Moreover, in the province of Mazandaran, women had significantly higher prevalence and YLD rates compared to men, which may also be due to the fact that the number of women working in the rice paddy fields is higher than that of men. In contrast, the lowest point prevalence of LBP was found in the East Azarbayejan province, and the lowest prevalent cases were observed in Ilam. In contrast to our results, a study conducted by Ghafouri et al found the lowest prevalence in Sistan and Baluchistan.13 The differences in these results might be due to the absence of an efficient registration system or the weak diagnosis of LBP in these provinces due to the low socioeconomic status, which may also lead to different findings each time the investigations are carried out. Furthermore, the lower rate observed in East Azarbayejan compared to other provinces might be explained by its relatively younger population, more active lifestyle (compared to provinces such as Tehran), as well as having a more efficient healthcare system during the measurement period (compared to provinces such as Ilam and Sistan and Baluchistan).

The current study also found that the incidence rate of LBP in females was highest in the 80-84 age group, which decreased with advancing age. This can be explained by the lower total population in the advanced age groups. In support of our findings, a study by Wang et al found that the global incidence of LBP also peaked in the 80–84 age group among females.25

The present study found no sex differences in the prevalence, incidence, and YLDs that were attributable to LBP in the geriatric population of Iran, which is in line with the findings of Wijnhoven et al.26 However, several different studies have demonstrated that the prevalence and incidence of LBP were higher among women in the general population.16,17,24,25,27,28 This contrast may be due to physiological differences between the two sexes in the reproductive ages such as pregnancy or contraceptive use. Anatomical and musculoskeletal differences may also play a role as men have greater muscular anatomy which provides better support for the vertebrae.29

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the burden of LBP among the elderly in Iran over the last three decades. However, this study has several limitations. First, in line with other GBD studies, there was limited actual LBP data available in Iran. Second, different definitions were used for obtaining an LBP diagnosis, which can affect the overall estimated burden. To resolve this issue, we used several adjustment models. Third, we did not report the burden of LBP according to the area of residence (rural/urban) or by race/ethnicity.

Conclusions

LBP is one of the most common public health complaints in the geriatric population of Iran. However, the burden of LBP varies by province, in accordance with their specific lifestyles. Although the prevalence, incidence, and YLD rates of LBP have not changed substantially over the past thirty years, the burden of LBP in the geriatric population of Iran remains high. To reduce the burden of this disease in the future, policymakers and the general population should be made more aware of LBP and its risk factors, and they should also provide LBP patients with both preventive and therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Institute for Health Metrics, Evaluation staff, and its collaborators who prepared these publicly available data. In addition, we would also like to acknowledge the support of the Social Determinants of Health Research Center at the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This study is based on publicly available data and solely reflects the opinions of its authors and not that of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Funding

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which was not involved in any way in the preparation of this manuscript, funded the GBD study. The Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 43004035) also supported the present report.

Data availability statement

The data used for these analyses are all publicly available at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

Ethical approval

The Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.616) approved the present report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplementary files

Supplementary file 1 contains Tables S1-S3 and Figures S1-S6.

(pdf)

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Ageing and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable Diseases. Key Facts. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- Naghavi M, Shahraz S, Sepanlou SG, Dicker D, Naghavi P, Pourmalek F. Health transition in Iran toward chronic diseases based on results of Global Burden of Disease 2010. Arch Iran Med 2014; 17(5):321-35. [ Google Scholar]

- Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Cross M, Hill C, Smith E, Carson-Chahhoud K. Prevalence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years due to musculoskeletal disorders for 195 countries and territories 1990-2017. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021; 73(4):702-14. doi: 10.1002/art.41571 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Naghavi M, Abolhassani F, Pourmalek F, Lakeh M, Jafari N, Vaseghi S. The burden of disease and injury in Iran 2003. Popul Health Metr 2009; 7:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-7-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thelin A, Holmberg S, Thelin N. Functioning in neck and low back pain from a 12-year perspective: a prospective population-based study. J Rehabil Med 2008; 40(7):555-61. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0205 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kent PM, Keating JL. The epidemiology of low back pain in primary care. Chiropr Osteopat 2005; 13:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-13 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med 2005; 62(12):851-60. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.015842 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018; 391(10137):2356-67. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30480-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Michel JP, Sadana R. “Healthy aging” concepts and measures. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017; 18(6):460-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.03.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morris LD, Daniels KJ, Ganguli B, Louw QA. An update on the prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018; 19(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2075-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vujcic I, Stojilovic N, Dubljanin E, Ladjevic N, Ladjevic I, Sipetic-Grujicic S. Low back pain among medical students in Belgrade (Serbia): a cross-sectional study. Pain Res Manag 2018; 2018:8317906. doi: 10.1155/2018/8317906 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri M, Teymourzadeh A, Nakhostin-Ansari A, Sepanlou SG, Dalvand S, Moradpour F. Prevalence and predictors of low back pain among the Iranian population: results from the Persian cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022; 74:103243. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103243 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396(10258):1223-49. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30752-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Chen M, Wu X, Lin S, Tao C, Cao H. Global, regional and national burden of low back pain 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. J Orthop Translat 2022; 32:49-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.07.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Noormohammadpour P, Mansournia MA, Koohpayehzadeh J, Asgari F, Rostami M, Rafei A. Prevalence of chronic neck pain, low back pain, and knee pain and their related factors in community-dwelling adults in Iran: a population-based national study. Clin J Pain 2017; 33(2):181-7. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000396 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(6):2028-37. doi: 10.1002/art.34347 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010; 24(6):769-81. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lyu FJ, Cheung KM, Zheng Z, Wang H, Sakai D, Leung VY. IVD progenitor cells: a new horizon for understanding disc homeostasis and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019; 15(2):102-12. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0154-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Chen S, Li Z, Deng X, Huang D, Xiong L. Mechanisms of endogenous repair failure during intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019; 27(1):41-8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.08.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Liu S, Ma K, Zhao L, Lin H, Shao Z. TGF-β signaling in intervertebral disc health and disease. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019; 27(8):1109-17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Blyth FM, Noguchi N. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and its impact on older people. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2017; 31(2):160-8. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2017.10.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Biglarian A, Seifi B, Bakhshi E, Mohammad K, Rahgozar M, Karimlou M. Low back pain prevalence and associated factors in Iranian population: findings from the national health survey. Pain Res Treat 2012; 2012:653060. doi: 10.1155/2012/653060 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ye H, Li Z, Lu C, Ye J, Liao M. Epidemiological trends of low back pain at the global, regional, and national levels. Eur Spine J 2022; 31(4):953-62. doi: 10.1007/s00586-022-07133-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven HA, de Vet HC, Picavet HS. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is systematically higher in women than in men. Clin J Pain 2006; 22(8):717-24. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210912.95664.53 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sandoughi M, Zakeri Z, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Davatchi F, Narouie B, Shikhzadeh A. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in southeastern Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study). Int J Rheum Dis 2013; 16(5):509-17. doi: 10.1111/1756-185x.12110 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mehrdad R, Shams-Hosseini NS, Aghdaei S, Yousefian M. Prevalence of low back pain in health care workers and comparison with other occupational categories in Iran: a systematic review. Iran J Med Sci 2016; 41(6):467-78. [ Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. Risk factors for low back pain in women: still more questions to be answered. Menopause 2009; 16(1):3-4. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818e10a7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]